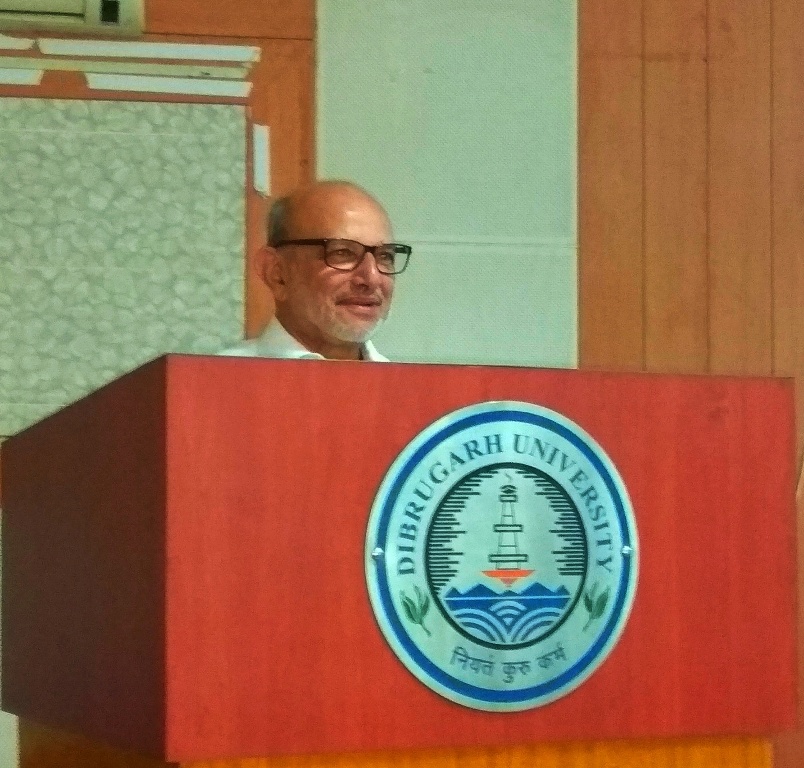

The Dibrugarh University organised a Colloquium on The Making of Indian Foreign Policy since Independence under the aegis of the Foreign Policy Lecture Series of the Ananta Centre, New Delhi and with support from the TATA on June 5, 2018. Mr. Rajendra Abhyankar, former Ambassador of India to the European Union, Belgium and Luxemburg and currently the Professor of Practice of Diplomacy and Public Affairs, School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, the US delivered the lecture.

Ambassador Rajendra Abhyankar began his address by stating that foreign policy as a discipline has been barely understood and discussed upon at the popular level in India owing to its formulation and execution within the exclusive confines of the Indian Foreign Service (IFS) and the highest decision-making committees of the Executive branch of government. In fact, he narrated how the then Foreign Minister, Mr. Atal Behari Vajpayee, jocularly addressed the mandarins of the IFS, in 1977, as being involved only in Bhojan, Bhraman, Bhashan (Food, Travel and Lecture). The first time in independent India’s history when it actually breached this information vacuum was in 2003, during the USA’s invasion of Iraq with people pouring out into the streets openly criticising the former’s action.

Foreign policy, to him, not only involves the need to locate and fix clear cut goals, but also requires the formulation of operating principles to follow and execute them in the pursuit of national interests. He underlined that in the Nehruvian era, it remained as the personal domain of the Prime Minister, and rarely was the Parliament and the bureaucracy allowed taking charge of issues. However, a significant change came with the sweeping changes emerging in the political landscape of India, when the late 1960’s onwards the regional parties gained power in the both states and at times at the centre. This resulted in local issues jostling for space in foreign policy decision-making. Some noted examples can be Indian involvement in the internal political processes of Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka owing to local pressures in the states of India’s Northeast, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Sikkim, and Tamil Nadu respectively.

The Speaker covered a wide range of issues including the entire gamut of international relations and area studies. When speaking of India’s neighbourhood, for example, he stressed that India has been progressively losing its pre-eminent position owing to aggressive manoeuvres of China, tailed by Pakistan, aided by short-sighted policy measures adopted by successive governments. Though we face continuous threats of terrorism from Pakistan, the USA will not chastise the former in our favour as long as it is involved in managing the affairs in Afghanistan. Further, in future, he sees the possibility of the Indus Water Treaty of 1960 being used as a tool by India against Pakistan if it continues to bleed India through hostile acts. Water issues would gain predominance in the South Asian region wherein, a joint cooperation mechanism has to be built by India and Bangladesh to deal with China over the Brahmaputra river water sharing as lower riparian countries. Similarly, both the countries need to cut a deal on the Teesta river water sharing as early as possible.

Another area of concern is the West Asian region, particularly the Persian Gulf, where almost 5 million Indian expatriates are working in various capacities. With Syria and Yemen in turmoil, in addition to the earlier conflicts in Iraq and Palestine, spill-over effects in the region could be a distinct possibility in the coming days. Evacuating such a huge population would prove to be a Herculean task given the logistics involved. India, therefore, maintains close cooperation with the intelligence agencies of all the countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council.

When it comes to the USA, he feels that the best years were during the presidency of George W. Bush, who had taken upon himself the objective of integrating India within the international nuclear regime with the signing of the Indo-US Nuclear Deal in 2008. This deal catapulted India into the great power club to the vehement opposition and sheer annoyance of China and Pakistan. The Obama years had been good, although nothing much materialised on ground. He termed Donald J. Trump as a Transactional President whose approach to international affairs is shaped principally by a policy of give and take.

India’s clout in the international financial institutions increased following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, when she had lent INR 1 billion to the IMF so as to help finance the economies of the European Union to offset its negative fallout. To him, the EU has a an ambition bigger than its means, especially with Brexit and the weakening of the French economy. There was an exciting Q&A session.

Professor A.K. Buragohain, Vice-Chancellor made his concluding observations wherein he mentioned about the roles the Universities can play as diplomatic apparatus and as platforms for foreign policy initiatives.

In her Vote of Thanks Dr. Obja Borah Hazarika, Department of Political Science thanked the Ananta Centre for sponsoring the lecture. She also thanked Ambassador Rajendra Abhyankar for his brilliant discourse.